February 10, 2026 — 5:00am

Jett lay on his living room floor and asked himself: “What do I do?”

The 23-year-old had spent hours on the phone with police and other authorities after discovering his new job was an elaborate scam.

While lodging an online cybercrime report, the day turned into night. But the darkness that engulfed him was deeper than that, Jett recalled. He could feel it on his skin.

Gone was $23,000, including all his savings and his older brother’s, too.

Still on the ground, Jett turned his head and caught sight of the Lifeline number he’d jotted down and thought: “Now is a good time to ring them”.

In the lead-up to the rollout of Australia’s “landmark” new scam laws, a staggering number of Australians are still falling victim to fraud. Scam losses jumped 5 per cent in the year to December, according to Scamwatch data, as criminals continue to exploit popular communication channels – emails, social media and phone calls – with devastating impact.

Consumer and industry groups want the Scams Prevention Framework accelerated, warning that delays will allow mass fraud to persist.

Although the new obligations for banks, telcos and digital platforms will start rolling out from July, a key plank of the law, requiring businesses to share “actionable scam intelligence”, isn’t due to begin for almost another two years.

There are also growing concerns about yawning gaps in the framework, which does not yet cover key services commonly exploited by scammers, such as dating apps, superannuation providers, email, cryptocurrency exchanges and online marketplaces.

“Scammers need to be hit from all angles, given any weak links within the chain risk being exploited by criminals and could undermine the overall effectiveness of the framework,” said Australian Banking Association chief executive Simon Birmingham.

The new scam laws

From the middle of this year, Australia’s new scam laws will apply to banks, social media companies, search engines, instant messaging services and telecommunication companies, requiring them to take reasonable steps to prevent, detect and disrupt scams.

The laws set out six overarching obligations that will apply to affected industries, while industry codes may also spell out minimum steps for businesses to meet these obligations.

For example, social media companies may have to warn users who have interacted with scam advertisements, and telcos may need to create systems to identify suspicious call and messaging patterns, according to a position paper released by Treasury late last year.

Delays and gaps

However, peak bodies representing consumers, banks and telcos have warned that the changes could be undermined by a decision not to implement obligations to report “actionable” scam intelligence until the end of 2027.

In its submission to the Treasury position paper, the Australian Banking Association argued that enforcing the exchange of this high-value data would be one of the most effective elements of the law in reducing scam volumes, allowing businesses to disrupt scam networks.

Australians reported $335 million in scam losses to Scamwatch in 2025, though the real figure could be at least five times higher due to underreporting.

Stephanie Tonkin, the chief executive of the Consumer Action Law Centre, said the latest scam data highlighted gaps in the current framework. Last year, scammers used email more than any other contact method to target Australians, according to Scamwatch, but email providers won’t be covered by the new laws.

Likewise, dating apps and websites are also not included in the legislation, even though romance scams were the third most common scam impacting Australians in 2025.

One man on a disability support pension was coerced by scammers posing as romantic partners into sending an estimated $300,000 to $400,000 overseas, according to the Scam Victim Alliance.

Tonkin said these omissions and delays to implement the framework showed the government needed to be much more ambitious.

“We just see scammers, like water, find their way through,” Tonkin said. “Until you plug all the available holes, the scammer just chooses the next available option.”

The Australian Telecommunications Alliance, which counts Telstra and Optus among its members, called on the government to announce a timeline for when it would include other industries exploited by scammers in the scheme.

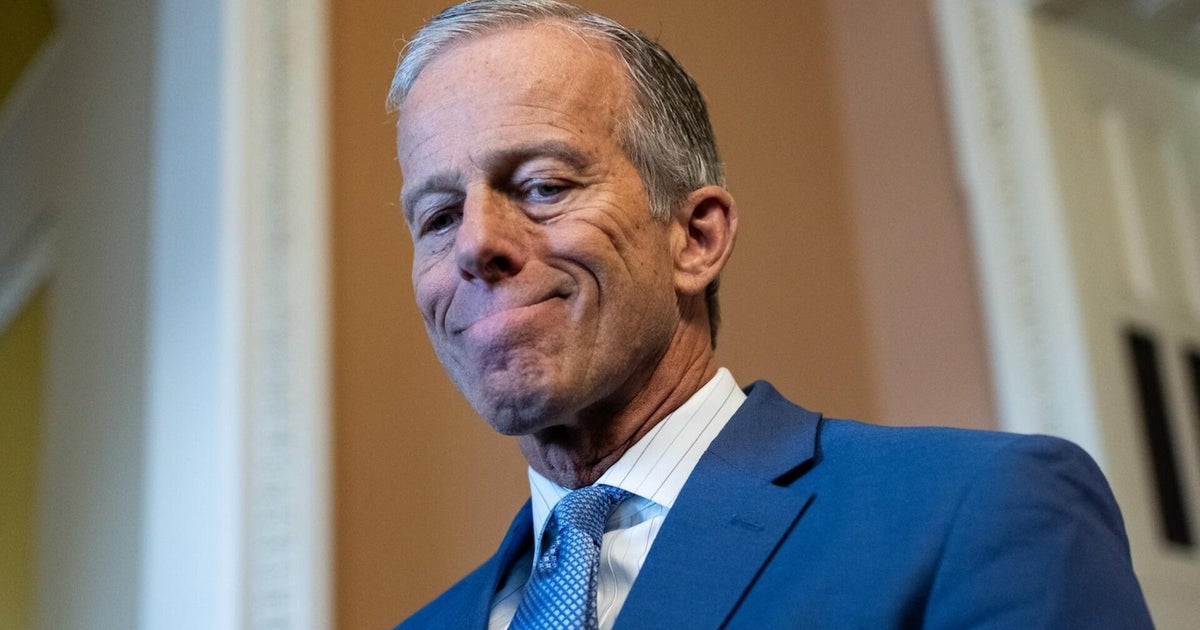

Financial Services Minister Dr Daniel Mulino did not respond directly to a question sent to his office about when the government was likely to announce such plans.

In a statement, Mulino said the Albanese government was “taking a co-ordinated approach to scams to ensure lasting protections, stronger trust, and better outcomes”.

“We encourage sectors to take voluntary actions to prevent and disrupt scams ahead being designated under the SPF. ”

The cost of scams

Jett, whose name has been changed, was first connected to fraudsters while using LinkedIn, a popular professional networking platform, to apply for jobs.

He spotted a data marketing role that looked perfect for his qualifications, and soon after, he was contacted by a recruiter.

The catch was that the full-time role was taken. Instead, they could offer Jett a part-time position that he could do remotely from his Melbourne home.

Jett had unwittingly signed up for a task-based employment scam where victims are used to complete simple duties (in Jett’s case, by promoting non-fungible tokens, a type of cryptocurrency asset). But to earn their commission, they have to invest their own money. The higher the potential commission, the larger the required investment.

Jett was coached by his trainer, “Adrian”, to upload his money using two separate cryptocurrency exchanges – services the government’s looming scam laws will not cover.

Though Jett initially suspected a scam, his concerns eased after he successfully withdrew $300 in “commissions”.

But on the fourth day, after Jett had already uploaded $23,000, he received a job that would require him to upload another $32,000. He instantly realised he had been swindled.

“I just wanted to cry so badly, but I couldn’t because I’m so stressed that I can’t even get my voice out,” Jett recalled.

“I was sitting in the living room and looking at the dark sky. I just feel like everything is dark.”

When Jett called Lifeline, a support worker encouraged him to take a single, simple step towards starting again. But even that has come with its challenges. Jett recently set his alarm early, planning to start going for daily runs, but found he couldn’t leave the house.

“Right now, it just changed my mindset that I don’t trust anyone.”

Lifeline’s chief research officer, Dr Anna Brooks, said it was common for people’s self-confidence to take a “massive hit”, and for their relationship to be strained with family members, after falling victim to a scam. Brooks said that Lifeline call takers would provide non-judgmental support, and she encouraged people to call even if they were not at a crisis point.

“We’re there for everyone,” she said. “Our trained crisis supporters, they’re there to have a conversation with people to maybe help them clarify their thoughts, [or] maybe help them think about what the next step is.”

If you or anyone you know needs support call Lifeline 131 114 or Beyond Blue 1300 224 636. For 24/7 crisis support run by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, contact 13YARN (13 92 76)